Diane Thomas

Dissertation for the MA in Medieval and Early Modern Studies (MT998)

Year of Submission: 2012

Motivations for the ‘Great Migration’

to New England 1628-1640:

the Case of the Hercules,

March 1634/1635

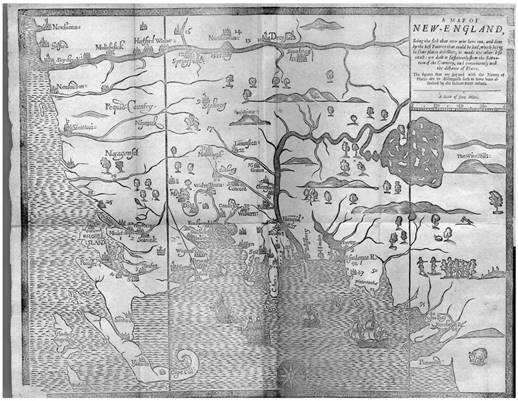

(William Hubbard’s Map of New England, 1621)

Diane Thomas

Dissertation for the MA in Medieval and Early Modern Studies (MT998)

Year of Submission: 2012

Word count in text, to the nearest thousand (excluding bibliography and appendices): 15000

Motivations for the ‘Great Migration’

to New England 1628-1640:

the Case of the Hercules,

March 1634/1635

Acknowledgements

My thanks for Jane Andrewes and Elizabeth Edwards for their advice on the Dutch community at Sandwich; and to Harris descendant Randy Harris for his information concerning the family of Hercules passenger Parnell Harris.

Contents

Page

1. Introduction……………………………………………………………… ….4

2. Historiography and Context……………………………………………….....7

3. The New England Colonies…………………………………………………10

4. The Hercules Passengers, Characteristics and Connections………………...13

4.1 The parishes they left………………………………….…………..13

4.2 Age………………………………………………………………...14

4.3 Occupation in England…………………………………………….15

4.4 Status and offices held in England………………………………...16 4.5 Education………………………………………………………….17

4.6 Pre-existing connections between passengers……………………..20

4.7 Connections with others not on the Hercules……………………..22

4.8 The servants………………………………………………..……...23

4.9 Were any of the Hercules emigrants from immigrant Dutch

or Walloon families?.......................................................................26

5. The Hercules and its Port of Departure…………………………………….27

6. Reasons for Going to New England………………………………………..30

6.1 Economic factors encouraging emigration………………………..30

6.2 Religious associations and problems……………………………...34

6.3 Other possible reasons for leaving England………………………37

6.4 The choice of New England over other destinations…..………….39

7. Preparing for the Journey……………………………………………….….40

8. Destinations and Outcomes………………………………………………...42

8.1 Establishing communities together…………………………….....42

8.2 Office-holding, achievements and influence……………….….….44

9. Conclusion…………………………………………………………….…....47

Bibliography…………………………………………………………….……..51

Appendix 1: Hercules Passengers, Parishes, Ages and Connections………....57

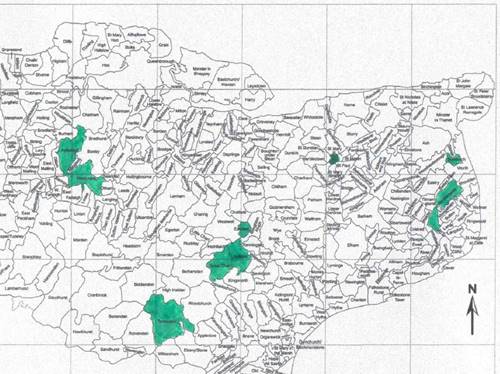

Appendix 2: Locations of the Kent Parishes the Hercules Passengers

came from…….………................................................................60

Appendix 3: Offices Held in England and New England…………………….61

Appendix 4: Connections between Hercules Passengers……………………..63

Appendix 5: Family Trees…………………………………………………….64

Appendix 6: Hercules Passengers: Connections with Separatist

John Lothrop & his father-in-law John Howse………………..68

Appendix 7: John Lothrop's Record of Early Houses in Scituate…………….70

Appendix 8: Hercules Passengers: English Home Towns and New England

Settlements……………………………………………………...72

1. Introduction

The Hercules sailed from Sandwich to New England in March 1634/5 carrying 102 men, women and children. Only fourteen years after the Mayflower, and four years after the founding of Boston, the Hercules made its journey at the start of the second phase of a movement which saw an estimated 20,000 English people emigrate to New England between 1628 and 1640. The first phase of some 2,500 migrants from 1628-1633 had been dominated by the Winthrop Fleet of eleven ships in 1630. Although the numbers involved were smaller than those going to some other American colonies in the same period, Americans call this the ‘Great Migration’, because they see it as a collective migration of Puritans and Separatists underpinning the Puritan character of New England.

Whilst many emigrants to New England 1628-1640 can clearly be seen as religious radicals, their religion may not have been the sole reason for their journey. Some may have had a complex mix of reasons, religion being just one, and which even they themselves may have been unable fully to unravel; others may not have been motivated by religion at all.

With a few exceptions, most research on the ‘Great Migration’ has been done in America. The most detailed profiles of the emigrants concentrate on the period after their arrival, though some studies have analysed sample groupings by factors such as age, occupation and even, to a restricted degree, family ties; and have looked for instances of religious problems before leaving England. Additionally, some families have researched genealogies going further back. This dissertation undertakes an in-depth study of passengers on the Hercules, particularly in relation to religion, status, education, occupation, friendship and family ties, in order to make sense of the conflicting findings of previous studies concerning the motivations behind the ‘Great Migration’ and re-examines some of the assumptions made. It looks at factors affecting the ability to influence both how New England developed and how it came to be perceived: the numbers who had held office, and levels of literacy and education. Where possible, comparisons are made with the findings of other studies of other emigrants to New England in the same period. For the main study of the Hercules passengers, the original documents used are: Kent parish registers; English wills of relatives of Hercules passengers; Kent town records; and ecclesiastical court records. Extensive use is also made both of American antiquarian works, which include transcripts of 17th-century New England church registers, wills of early settlers, and information about earliest land holdings in New England, and of biographical dictionaries of early settlers which base their profiles on sources such as freemen’s lists, and land and church records..

Whilst its passengers were not necessarily typical of the whole movement, the Hercules was chosen for the study because it is particularly interesting for several reasons. Of all the ships known to have gone to New England in this period, it was one of probably only two which sailed from Sandwich (the vast majority went from London). The passenger list shows that, with one exception, all the passengers were from Kent. Most of the emigrant ships carried people from more randomly scattered locations. The ship was jointly-purchased specifically for the voyage by several of those on board. Whilst there were other examples of ship-owning emigrants, the majority of voyages were commercial ventures, many arranged by the Massachusetts Bay Company. Many Hercules passengers can be identified as probable religious radicals by their names, and family members’ names, alone. One of the ship’s purchasers, surgeon Comfort Starr, was accompanied by his sister Truthshallprevail. Their siblings, not on board, included Jehosephat, Nostrength, Moregifte, Suretrust, Standwell, Constante, Joyful and Beloved. Joint owner, Nathaniel Tilden, had brothers Hopestill and Freegift. Also on board was Faintnot Wines.

Whilst documentation concerning the emigrants in New England is generally very full and often available in printed primary sources, there are problems concerning incomplete or varying records prior to departure, making overall quantification and comparison of the emigrants impossible. Nevertheless, the intention is to see how perceivable characteristics amongst the Hercules group, set in the context of religious, economic and other particular factors in the parishes and towns they came from, might contradict or support assumptions previously made about emigrants to New England, or suggest characteristics or motivations not previously considered.

2. Historiography and Context

The early view was that ‘the Great Migration’ was an exodus of persecuted religious radicals seeking to build their own ideal community from scratch. However, this view drew strongly on the writings of second and third-generation New Englanders, such as Cotton Mather, in the late 17th-century, after New England’s puritanical outlook was well-established, and was not necessarily an accurate reflection of the possibly complicated factors that had motivated the first generation to emigrate.

This view of religiously-motivated emigration persisted as the accepted one for over 200 years. Not until the early 20th-century did historians seriously put forward the opposing theory that the ‘Great Migration’ was heavily motivated by economic factors. Though academic interest in the subject temporarily waned after the mid-20th-century, renewed interest during the last thirty years has seen the debate continue, with some writers seeing only religious motives, but others taking a more balanced view, suggesting a complicated mix of motivations.

Some very obvious factors contrastingly give circumstantial support to both religious and economic causes of the ‘Great Migration’. On the one hand, its start in 1628 and end in 1640 exactly coincided with the rise and fall of anti-Puritan William Laud; and its second and stronger phase from 1634 followed Laud’s appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633. This was an era when radical clergy lost their livings, and their followers were often harshly punished. The return to England of many of the emigrants during the Interregnum offers further strong circumstantial evidence that they were Puritans or Separatists whose emigration had been motivated by a desire for religious and perhaps political freedom.

Important economic factors also coincided with the emigration, though less exactly than the religious ones, having begun well ahead of 1628. The early 17th-century was a time of rising food prices. Many emigrants came from East Anglia and Kent, both traditionally cloth-producing areas. This was a time when the traditional cloth trade was dwindling and small independent producers were losing out to larger enterprises. But the picture was mixed. In Kent, the New Draperies and emerging new industries meant the county suffered much less than other areas.

Individuals may have had many other reasons for emigration: fear of epidemics; overcrowding in the towns; land shortage in the countryside; peer-pressure; a desire for political and educational freedom; escape from the law, from debts, or from family responsibilities; the perceived opportunities in the new colony; even a desire to be Christian missionaries to the Native Americans, or just for adventure. Many of their reasons went unrecorded; some were documented in letters and diaries, but impossible to rank in order of importance.

James Truslow Adams in 1921 was the first to argue that economic causes were at least as important, if not more important, than religious ones. Economic causes were also stressed by N.C.P Tyack in 1951, who additionally suggested a political discontent and concern for personal freedom that went wider than the religious radicalism that underpinned Parliamentarianism. Breen and Foster, in 1973, attempted a statistical analysis of 1637 emigrants, concluding that “their motives…..were mixed, but for most religion was probably not incidental” and that to try to unravel them would be to seek to “separate the historically inseparable”. This idea of complicated inter-twining of motives was echoed by David Grayson Allen in 1981, although his main focus was the development of government and administrative structures in New England. Other late-20th and 21st-century writers have similarly moved away from the religious versus economic debate, leaving it still unresolved. American writers have more recently concentrated on how society was created in New England, though Virginia DeJohn Anderson also stressed the religious nature of the settlement. Two British writers, writing from the English perspective, have developed new themes: David Cressy studied the role of communication, in the form of letters, diaries and pamphlets, in persuading people to go, or not to go, to New England; Susan Hardman Moore examined the experiences of those who returned to England in the 1640s.

3. The New England Colonies

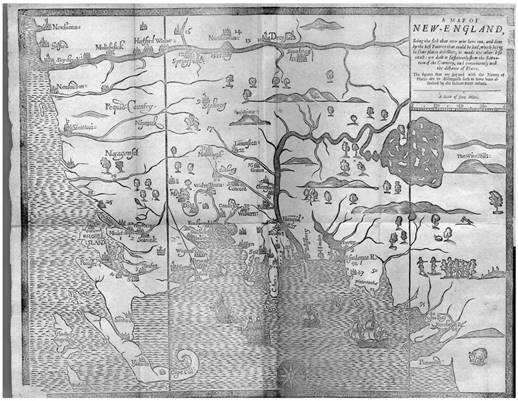

New England was made up of a number of colonies. Plymouth and Massachusetts, the most important during the Great Migration, had very different histories which may have translated into different motives amongst their settlers. Figure 1 shows the location of the colonies within New England.

Figure 1: New England Colonies

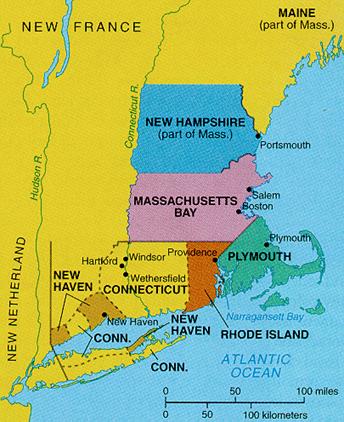

The original patent for the Mayflower in 1620 allowed it to take a group of the Separatist exiles, then in Leiden, and others from England, not Separatists, to settle the northern part of Virginia around present-day Manhattan. It was financed by the Adventurers, a group of around 70, formed especially for the project, some of whom were Separatists or Puritans themselves, but were nevertheless primarily entrepreneurs. They included big and small investors, all getting one share for each £10 invested. Whether by accident or design, the Mayflower landed instead further north at Plymouth Harbour, and that is where its Pilgrims settled. In 1621 a new patent was granted to cover the new territory. The Adventurers now effectively controlled an independent colony. But there quickly came a falling out. Despite large shipments of furs, and presumably timber whose price was soaring in England, there were financial losses. The settlers had large debts to the Adventurers. A new agreement was negotiated. The Adventurers sold all their interests for £1800 to eight of Plymouth’s leading men and four of the Adventurers who still wanted to be involved. This group, now called the Undertakers, took on all the debts in return for certain monopolies. Plymouth assumed self-government. Figure 2 shows the Plymouth Colony Settlements.

Figure 2: Plymouth Colony c.1690

Source: Stratton, op cit, p.12

In 1628 the New England Company was formed, succeeded by the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1629. They acquired a patent for land to the north of Plymouth on Massachusetts Bay. In 1630 Winthrop’s fleet of eleven ships went to settle this new colony. At this point the ‘Great Migration’ began in earnest. With their colony controlled by the Massachusetts Bay Company, the settlers here had less freedom for self-determination than their Plymouth counterparts. The Massachusetts Bay Company also took control of New Hampshire in 1641 and Maine in 1652, but did not take over Plymouth until 1691.

The first Europeans in Connecticut were the Dutch. However, settlers from Plymouth Colony and Massachusetts Bay moved in to found Hartford in 1636. John Winthrop junior played a big part here and was an early Governor of Connecticut. Also in 1636, groups from Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay moved across to form the small colony at Providence.

4. The Hercules Passengers, Characteristics and Connections

4.1 The parishes they left

Appendix 1 shows the full Hercules Passenger list in its original order and the places of origin they gave. From research in original parish registers, parish of baptism and age have been added, where possible, as well as connections to other passengers. All on board, except Parnell Harris from Bow, London, and the Hayward family from Aylesford, in West Kent, were listed as coming from East Kent. Parnell was in fact baptised at Northbourne where members of her immediate family continued to live.

Appendix 2 is a map showing the parishes the Hercules emigrants gave as their pre-departure homes. Whilst these are often different to parish of baptism, a degree of movement is not unexpected. For the families, the home parish stated is in most cases where they baptised their children, except for three, all of whom were stated as coming from Sandwich. Of these, the Hatch family had baptised their youngest children (aged 3 to 9) at Wye; Thomas Besbeech had baptised his children at Frittenden a decade earlier, and buried his wife Anne there just 11 months before the Hercules sailed; Jane Egelden, travelling with the Besbeech family, had baptised children at Biddenden in May 1632 and November 1633. Her husband Ambrose did not arrive in America, but whether he died in England or at sea on another ship is unclear. All three families might simply have settled at Sandwich in the months before departure, but no Egelden or Besbeech was found on the Sandwich assessment for ship money dated 30 December 1634, though at St Mary’s Sandwich a “----Hatch” was listed, consistent perhaps with William having just arrived and his first name not yet well known. It was Thomas Gardiner, vicar of St Mary’s, long known as a Puritan parish, who signed the Hatch certificate of honesty and religious conformity prior to the voyage. As a recent widow, Jane Egelden may simply have been staying with friends or relatives; but the Besbeech family was of some standing, and if there they would surely have been listed on the Ship Money assessment. They may have given Sandwich as their home either for convenience, or because they could not get their certificate signed at Frittenden.

4.2 Age

When Nathaniel and Lydia Tilden left for New England they were aged 51 and 48 respectively, their six children who accompanied them between five and 24. Comfort Starr and widower Thomas Besbeech were both 45 and accompanied by teenaged children; widow Emme Mason, travelling with her son, was 51, and two other passengers, single man Faintnot Wines and servant William Holmes, were over 40. Table 1 compares the ages, where known, of passengers on the Hercules with those of passengers on seven 1630s ships to New England studied by Virginia Anderson, those on all ships from East Anglia to New England 1629-1640 studied by NCP Tyack, and 110 emigrants to New England from Wiltshire 1635-38 studied by Anthony Salerno. Many of the passenger lists, including that of the Hercules, did not give ages. The ages of the Hercules passengers come from research undertaken for this study. Ages of the groups studied by Anderson, Tyack and Salerno come from the passenger lists. This makes direct comparison difficult because, when researching the parish registers, it was easier to find definite, and thus usable, information for complete families than for single adults, so ages of less single people were found. This may partially explain the apparent greater percentage of young children, and smaller numbers of young adults on the Hercules. Nevertheless, it can be seen that the numbers of over-40s on the Hercules were almost exactly in keeping with the groups studied by Anderson and Tyack, and Nathaniel Tilden and other over-40s with him were in no way unusual. To undertake such a journey and such an upheaval of life-style at their age, they must either have feared very greatly for their own futures, or those of their families, in England; or they must have perceived New England as offering some wonderful opportunity.

By contrast, Salerno’s study of 110 Wiltshire migrants to Massachusetts 1635-1638 found a much younger profile, the group made up of 52 single males, 4 single women, 28 husbands and wives and 26 children under 16. The reason why Salerno’s Wiltshire migrants included a higher proportion in the 21-30 age group, and a much higher proportion of single males, may have been that these included more purely economic migrants. This would support Flisher’s view that “prevailing economic difficulties in the cloth trade in the 1630s may have provided a stimulus to emigration, but this was less important in Cranbrook than in Wiltshire”.

Note: Salerno did not breakdown the ages of the four people he found over

age 40. These have been assumed to be 41-50 for ease of comparison

4.3 Occupation in England

Table 2 shows a breakdown of occupations amongst the emigrants before they left England (many trades, especially in the cloth trades, could not be supported in New England and those concerned mostly turned to agriculture on arrival). The Hercules figures are again compared to the studies by Anderson and Tyack.

The Hercules passengers can be seen to have included a broadly similar proportion of those involved in agriculture as the East Anglian emigrants; and a similar number of cloth trades practitioners to the seven ships sample. In terms of other artisans they were similar to both. The last group, professional, includes clergy, and gentry (of whom there was only one representative overall). The very high proportion in the East Anglian group is due to the high number of clergy among them, almost certainly demonstrating a high instance of religiously-motivated emigration from East Anglia.

4.4 Status and offices held in England

The simple division of occupations shown in Figure 2 hides great variations in status, the cloth trades encompassing all from humble weavers to rich mercers; agriculture all from farm labourers to rich yeoman. The Hercules in fact carried a number of high status people. Appendix 3 shows the offices they are known to have held in both England and New England. Nathaniel Tilden had been mayor of Tenterden in 1622. His cousin John Tilden succeeded him in the position in 1623; and his uncle John Tilden had held it in 1586 and 1601. His wife’s brother, Thomas Huckstep was to become Tenterden mayor in 1641. His brother Hopestill Tilden was Common Councillor at Sandwich from 1619-1640 and described by Ollerenshaw as a member of the town’s civic elite. Fellow passenger Jonas Austen was first cousin to John Austen mayor of Tenterden in 1634, who signed the certificates of honesty and conformity enabling the Austen, Tilden, Hinckley and Lewis families to leave England. Though not obviously connected to the others from Tenterden, Samuel Hinckley, who had lived there for around ten years, had a son at Trinity College Cambridge who was to become the Governor of Plymouth Colony. Comfort Starr was the grandson of Thomas Starr who was mayor of New Romney at the time of making his will. William Hatch, cousin to both Tilden and his wife, and Thomas Besbeech, probable cousin to the Austens, probably also moved in that same civic elite circle, whilst William Witherell was a church minister, although a schoolmaster rather than caring for a parish. Together with their wives and families, this group made up 41% of those on board. Of the remaining adult males, excluding servants, Robert Brooke was a mercer, so probably of some standing; eight were artisans, and little is known about the rest.

4.5 Education

Four of the families on the Hercules had known university connections in England. Passenger William Witherell, curate at Boughton Monchelsea in 1626, and later a schoolmaster at Maidstone Grammar school, graduated MA from Corpus Christi in 1626. His contemporary at Cambridge, though at Emmanuel College, was another clergyman, Freegift Tilden, rector of Langley in Kent from 1627-1637 and brother of Nathaniel Tilden on the Hercules. Another of Nathaniel’s brothers, Theophilus, matriculated at Magdalen Hall Oxford in 1610, but died soon afterwards. Also on the Hercules was the Hinckley family of Tenterden whose eldest son Thomas, future Governor of Plymouth Colony, followed later, having entered Trinity College Cambridge in 1633. Finally, Thomas Starr, father of Hercules passenger Dr Comfort Starr, matriculated sizar from Emmanuel College Cambridge in 1585. Comfort himself and his son Comfort junior were, as will be seen later, important figures in the early history of Harvard.

In an age when university education was rare, the fact that four of the Hercules families had these university connections suggests that education was important to this group. In fact many of those on board had some standard of education. Almost all came from towns, or the vicinity of towns, that had grammar schools before 1600: Sandwich, Wye, Tenterden, Biddenden, Maidstone and Canterbury. Though records do not exist to say whether any Hercules passengers attended them, the fact that a good number on the ship were of ‘the middling sort’ makes it a reasonable possibility. The probate inventory for Hercules passenger Emme Mason from Eastwell shows that she left a bible, a psalm book, a sermon book and 11 other books, total value 29s 10d out of goods and property, including her house and acre of land, valued in total £25 16s. Nathaniel Tilden’s inventory included 46 books and religious works, value £5. Thomas Hayward’s inventory included a bible, nine other religious works and some small books, total value £5 13s 4d. Comfort Starr’s inventory included books to value £7. Amongst the servants, Thomas Lapham’s 1648/9 inventory included ten books value 13s 4d.

Table 3 shows likely literacy and education amongst Hercules passengers based on university connections, ownership of books and ability to sign documents. Many people who could not write could nevertheless read to some extent, but that ability left behind little evidence. This probably explains the one person who signed by mark, but had books listed in their inventory, although ownership of books might not have meant ability to read them if, say, they were inherited. All adults, including servants and children over 16, have been included in the survey. Unfortunately of the 53 people, evidence was found for only 21. In some cases, evidence is lacking because a will found in transcript form does not show signature; but in most cases it is because no evidence was found that the person left a will or bought land, many of these being women. However, where these were men, lack of a will or property probably suggest lower status and less likelihood of literacy, so the figures obtained may slightly over-estimate literacy in the group as a whole.

Sources: http://venn.lib.cam.ac.uk/Documents/acad/enter.html A Cambridge

Alumni Database; Anderson, Robert, op cit, vols. 1-7 http://www.histarch.uiuc.edu/plymouth/searchform.html Plymouth Colony

Archive Project; http://teh.salemstate.edu/Essex/essexprobate.htmlEarly Essex

County Probate Inventories

Table 4.1 shows Cressy’s findings for the social structure of illiteracy and Figure 4.2 comparative figures for Hercules passengers, although again direct comparison is difficult because the geographical area is different, because Cressy’s figures exclude servants, an important group on the Hercules, and because it might be assumed that the many for whom no data was found were people less educated and less likely to create paperwork.

Table 4.1: Social structure of illiteracy in the diocese of London, Essex and Hertfordshire, 1580-1640

Social Group |

No. sampled |

No. mark |

% mark |

95% confidence interval |

Clergy/professions |

177 |

0 |

0 |

- |

Gentry |

161 |

5 |

3 |

+/-3 |

Yeomen |

319 |

105 |

33 |

+/-5 |

Tradesmen/craftsmen |

448 |

188 |

42 |

+/-5 |

Husbandmen |

461 |

337 |

73 |

+/-4 |

Labourers |

7 |

7 |

100 |

- |

Women |

324 |

308 |

95 |

+/-% |

Source: Cressy, David, Literacy and the Social Order (Cambridge, 1980), Table 6.4, p.121

Table 4.2: Literacy on the Hercules by social structure of people over 16

Social Group |

No. on board |

No. for whom Info found |

No. mark |

% mark |

Clergy/professions |

5 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

Gentry |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Yeomen |

2 |

2 |

1 |

50 |

Tradesmen/craftsmen |

9 |

4 |

2 |

50 |

Husbandmen |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Male Servants |

13 |

5 |

3 |

60 |

Labourers |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Unknown |

3 |

0 |

- |

- |

Women |

23 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Note: adult sons have been allocated the same social group as their fathers

Source: Information from Anderson, Robert, op cit , vols. 1-7

4.6 Pre-existing connections between passengers

Virginia Anderson points out that while no population of migrants ever precisely replicates the population of its original society, and 17th-century emigrants from the British Isles to the New World were generally overwhelmingly young, male and unmarried, those involved in the ‘Great Migration’ to New England resembled much more closely the demographic structure of the British population. In the seven ships she studied, nearly 90% travelled in family groups of some sort and 75% in nuclear family units. She perhaps ignores that sometimes members of nuclear families all travelled, but not all as one group. For example, Comfort Starr had a wife and eight children who marriage, burial and university records show all went to New England, but he travelled on the Hercules without his wife and with only three of his children; Margaret Johnes was travelling to join her husband William. In addition, four people on the Hercules who initially look like single travellers were shown by research to actually be travelling with family: Emme Mason and Josiah Rootes were mother and son; Parnell Harris and James Sayers were step-siblings.

Of the 102 people on the Hercules, 73 (72.3%) were travelling in some sort of family group, 65 (64%) in a nuclear family, less than in Virginia Anderson’s seven ships study. 21 (20.8%) were servants; and 7 (6.9%) were travelling apparently alone, although of these three were friends and one going to join her husband. Furthermore, a number of the families were connected, as Appendix 5 shows: William Hatch was first cousin to Lydia Tilden and second cousin to her husband Nathaniel. Jonas Austen was cousin to Parnell Harris and James Sayers, and these three were probably also related to Thomas Besbeech. James Bennett, Tilden servant, was brother to Jane Egelden who, with her children, travelled with the Besbeech family, although how or if they were related to the Besbeeches is unclear. James Bennett and the Egeldens may also have been connected to William Hatch, as William returned to England and travelled out again with Stephen and Elizabeth Iggulden, sister and brother-in-law of Jane and James Bennett, in 1638 on another ship he part-owned, the Castle. There were also apparent or possible friendship connections. Nathaniel Tilden witnessed the will of Constance Austen’s first husband William Robinson; William Witherell was at Cambridge with Nathaniel Tilden’s brother Freegift; Thomas Boney and Henry Ewell, shoemakers from Sandwich, were listed together on the passenger list as one family group; listed immediately above them was Faintnot Wines who bought land with Thomas Boney in Charlestown; also listed together were Thomas Rootes, his mother Emme Mason and John Best and these three settled together at Salem away from the rest. Appendix 4 shows this web of interconnections in diagrammatic form, demonstrating that the Tilden family had the most connections to others on the ship. As Nathaniel Tilden was listed first on the passenger list and was part-owner of the Hercules, it can be assumed that he was most instrumental in bringing the group together. There were a few for whom no connections were obvious, but no doubt there were other connections that have not been found; and there were also religious connections which will be dealt with separately in section 6.2 and Appendix 6.

4.7 Connections with others not on the Hercules

A number of Hercules passengers had connections with other migrants, and again it was Nathaniel Tilden who was most connected. In a connection apparently overlooked by the many writers on aspects of the ‘Great Migration’, Tilden was step-brother to Robert Cushman who negotiated with the London Virginia Company the patent for the Leiden separatists to go to New England on the Mayflower in 1620. Cushman himself followed on the Fortune in 1621, along with his 12-year-old son Thomas, but apparently leaving behind his five-year-old daughter Sarah. He died in 1625. Nathaniel’s brother Joseph, citizen and girdler of London, but clearly the same Joseph from his will, was one of the Adventurers, who financed the Mayflower. Another was Timothy Hatherley, friend of Nathaniel Tilden, who was to become Lydia Tilden’s second husband after the death of Nathaniel. In 1627 Hatherley became one of the Undertakers who took control of Plymouth, and as a result he was awarded a large parcel of land at Scituate, where Nathaniel and a large group from the Hercules settled. With Nathaniel having these connections, it seems probable that his younger brother Thomas was the Thomas Tilden who sailed on the Anne in 1620, though Robert Anderson disagrees, saying he found no obvious connection.

John Lewis had an older brother George who, like him, settled in Scituate. Thomas Besbeech was brother-in-law to Patience Foster who went to New England in 1635 on the Elizabeth with her son Hopestill. It seems likely that Nathaniel Tilden was also related to Patience through the Bigge family (his mother’s and Patience’s maiden name) and that view is strengthened by the repetition of the unusual name Hopestill, which was also the name of Nathaniel’s brother. Also almost certainly related to Patience Foster (nee Bigge) was Comfort Starr whose brother Moregifte had married Rachel Bigge at Biddenden in 1617. Probable sisters Rachel and Patience were baptised at Cranbrook in 1594 and 1588, but Patience’s parents are not named. Parnell Harris was going to join her brothers William and Thomas and sister Jane who emigrated around 1634. Margaret Johnes was going to join her husband “William Johnes late of Sandwich, now of New England, painter”. Jane Egelden and James Bennett were followed to New England in 1638 by their sister Elizabeth. Rose Tritton was following her sister Bennett and brother-in-law Thomas Stanley who, by the dates and locations of their children’s baptisms, must have travelled to New England in 1634. Comfort, as already seen, was joined later by his wife and youngest children. He was also joined in 1637 by his brother Thomas, who sailed on the only other ‘Great Migration’ ship known to have departed from Sandwich, name unknown; and, by 1642, by his sister Suretrust and her husband Faithful Rouse.

4.8 The servants

The 21 servants on the Hercules are an interesting group. Whilst a few of them clearly were true servants, a few definitely were not, and the status of many as servants is questionable. It seems likely that many of the servants were not of the serving class as such, but family members, or young adults, the children of friends, under protection of the head of household. The cost of passage, supplies and tools was not inconsiderable; and a lot of work was needed to prepare a settler’s land and home on arrival. Thus, as Cressy explains, “migrants who were willing to become servants for three or five years could more readily find sponsors for their passage”. Another factor could be that each household needed a certificate of religious conformity. Those who might have difficulty obtaining one might attract less notice if listed as a servant of someone else.

Of the 21 servants on the Hercules, Sarah Couchman, servant to Nathaniel Tilden, was probably his step-niece, daughter of Robert Cushman; and Truthshallprevail Starr, servant to Comfort Starr, was in fact his sister. Others who were probably not true servants were Thomas Lapham and George Sutton, listed as Tilden servants, but who married two of the Tilden daughters, Sarah and Mary on the same day, 13 March 1636/7 at Scituate. In a small community of like-minded people, marriages across the class divide were probably not unusual, but the Tildens seem to have been near the top of the social scale in New England, and least likely to let their daughters marry servants. Further evidence suggesting that these two were not servants is that the inventory of Thomas Lapham included ten books value 13s 4d, perhaps a lot of books for someone who had been a servant; and George Sutton’s brother Simon, himself listed as a Hatch servant, witnessed Nathaniel Tilden’s will in 1641. Also listed as a Hatch servant was William Holmes, whose death record shows was already 43 when the Hercules sailed. At first sight he would seem to have been a servant of many years, but he left service by 1638 when he signed the oath of allegiance, and he signed as William Holmes senior, suggesting he already had an adult son in the colony, which would have been difficult for a servant. He married for a second time around 1640 and Mary, daughter from that marriage, married Thomas Tilden, grandson of Nathaniel and Lidia, at Marshfield in 1664/5. Furthermore, William Holmes’ inventory included six books. Joseph Pacheing’s status as servant is also called into question because he married into the household of his employer. He travelled on the Hercules as a servant of Thomas Besbeech. Also in the Besbeech household, though relationship unclear, were Jane Egelden nee Bennet and her children (see Appendix 1). In 1642 at Roxbury Joseph married Jane’s widowed sister Elizabeth Iggulden nee Bennett.

Also not a servant in any true sense, as he cannot have served out a contract of any length, was Joseph Ketcherell. He was in Charlestown in 1635, whilst his Hatch employers, settled in Scituate. No baptism records for Joseph, or for Symon Ketcherell, also a Hatch servant, have been found at Sandwich; and also no record of Symon after he reached New England. However marriages and baptisms of Ketcherell were found at Sandwich 1580-1620: David Kecherell married Alice Byshopp at St Peter’s in 1609/10 and baptised Benjamyn 1617 and Samuell, 1619 at St Clements; in addition there were three children of John Ketcherell, John 1597/8 at St Peter’s, and Steven 1603 and again in 1620 at St Clements. David’s son Samuel is particularly interesting as he is probably the one who died at Springfield, Massachusetts in 1651, believed by amateur American researchers to have been born in Kent around 1619, although they have not found the Sandwich baptism. It seems likely that Joseph and Simon were either other sons of David and Alice born between 1610 and 1617, or of John born after 1603, or at least close relatives. The Sandwich town book shows that in 1615, David Ketcherell and Hopestill Tilden (Nathaniel’s brother) were the constables for Sandwich, along with a John Ewell who could have been related to Hercules passenger Henry. David Ketcherell served as constable in most years up to 1629. In a later generation, Thomas Ketcherell, gent. died in 1774 aged 61 at St Peter’s Sandwich. Together these small facts suggest that the Ketcherells moved in possibly similar circles to the Tildens and that Joseph and Symon were more likely to have been on the Hercules under the protection of William Hatch rather than as true servants.

James Bennett and Rose Tritton probably signed on as servants as a way of financing their emigration. He had inherited just £10 from his father’s will, insufficient to finance emigration; she, as already seen, was joining her sister and brother-in-law, although records in New England show him to have been prosperous.

Two who seem definitely to have been true servants were Edward Jenkins, who was still a servant with time still owed on a covenant of service when Tilden made his will in 1641, and Samuel Dunkin who Robert Anderson records as having been a servant in both England and New England. Apart from one probable baptism, no records of the remaining eight were found in England or New England. These could have been travelling under assumed names; died at sea, quickly returned home or moved on elsewhere.

4.9 Were any of the Hercules emigrants from immigrant Dutch or Walloon families?

With their apparent Puritan sympathies and several strange-sounding surnames it seemed likely that some of the emigrants were from former immigrant families, but no connections were found. That does not rule out the possibility of immigrants amongst them. In particular, Perien could be French, and Couchman/Cushman Dutch, but even Brooke could be derived from Dutch, especially in the case of a mercer. Tilden also sounds possibly Dutch, but several Tilden wills had been proved in the Canterbury probate courts as early as the 1400s, so the family was long-established in Kent.

5. The Hercules and its Port of Departure

Comfort Starr made a deposition on 2 February 1634/5, saying the Hercules belonged to him and fellow passengers Nathaniel Tilden and William Hatch, John Witherley, who was to be the ship’s master for the voyage, and a Mr Osborne; and that John Witherley, a mariner of Sandwich, had bought the 200-ton Flemish-built ship, previously named St Peter, on their behalf for £340 at Dunkirk the previous November. Starr said “being noe seaman, [I] cannot tell of what length, breadth or depth she is, but guess her to be about twelve foote broad above the hatches, fowerscore foote longe, and six-teene foote deepe”. A small space, then, for the 102 people who undertook the voyage to New England. The ship was taken to Sandwich to be fitted out for the voyage four months later.

Although Starr apparently had no shipping knowledge, and, as a surgeon, possibly no business sense, Sandwich merchant William Hatch possibly did have the necessary experience, and Nathaniel Tilden, as already seen, was brother to Adventurer Joseph Tilden. In Sandwich, his brother Hopestill Tilden was a grocer and the will of Hopestill’s widowed daughter-in-law dated 1637 included raisins and currants with total value £7 as well as white and brown sugar value £1 7s. She was clearly in the grocery business too, with experience of importing, and this probably also applied to Hopestill. This raises the question whether the Hercules was a business venture for some of its passengers, though Tilden, Starr and Hatch did all settle in New England, and Starr, as will be seen, seemed to have had a different purpose, concerning education. Virginia Anderson points out that if the Hercules owners charged the same rate as did the Massachusetts Bay Company (£5 per adult with a reduction for children) they would have raised between £300 and £500. Having covered their outlay in one journey, the ship would then have been in full profit taking goods back to England on its return and on any subsequent voyage. However, the wills and inventories of Tilden (1641), Hatch (1651) and Starr (1659) make no mention of any ship, so any enterprise of that sort seems to have been short-lived, although Hatch was also part-owner of the Castle in 1638. Owners travelling to New England on their own ship were not totally unusual. Thomas Paine and Benjamin Cooper owned shares in the Mary Anne on which they travelled in 1637. Cooper died on the voyage, Paine still owned his share when he wrote his will just seven months later. Nevertheless, it is unclear how many passengers owned substantial shares like the Hercules owners, and how many were actually settlers as opposed to visiting for business reasons. This, and the reasons why, could be an interesting topic for further research.

It is unclear whether the Hercules made any subsequent trans-Atlantic voyage. Sandwich town records record, but do not name, a ship sailing to “the American Plantations” in 1637, carrying around 80 passengers. The first passenger listed was Thomas Starr, brother of Comfort, who settled in Boston. It seems quite possible that this was the Hercules again, especially as this was the only other known ‘Great Migration’ ship definitely known to have left from Sandwich, verified by a search of the town book from 1628 to 1640. In fact ships making successive journeys to New England seem to have been pretty rare. The James which sailed London to Boston in 1632 and Gravesend to Salem in 1633, both times captained by a Mr Grant, is one example. Another was the Lyon, which made four trips between 1629 and 1632, all captained by William Pierce. There is no complete list of ships, but an effort to compile one has resulted in the Pilgrim Ship Lists Early 1600s website which lists some 250 ships which sailed to America before 1640. This includes either passenger lists or more restricted details of around 70 ships that sailed from English ports to New England between 1628 and 1640, perhaps a third of the total. Of these London was the start for 38, whilst the 11 Winthrop ships sailed from the Isle of Wight in 1630. No other port on this list accounted for more than five ships, so even this very incomplete list demonstrates that Sandwich was not unusual in sending only two. None are listed from Dover, two from Gravesend. All but nine Hercules passengers were from East Kent, so Sandwich does seem a logical place to have sailed from. However, if any on board were fugitive Separatists, then Sandwich, as a less common emigration point, might have attracted less attention, especially for passengers sailing in their own ship. Fourteen on board had their certificates signed by the vicar of St Mary’s Sandwich, the church used by the Dutch Congregation and long known as a radical stronghold. Owner Nathaniel Tilden’s brother Hopestill was a Common Councillor at Sandwich. As a member of the local elite he would have known people who could smooth the way for the Hercules, if necessary. A further 32 had certificates signed by John Austen, mayor of Tenterden, who was related to the Tildens and Austens.

6. Reasons for Going to New England

This chapter looks both at factors, whether general, personal to the emigrant or affecting the place where they lived, that might have motivated them to emigrate, and at those which might have prompted them to choose New England over more convenient locations.

Winthrop set out his own reasons in 1629, though much of what was published then was little more than propaganda. In summary, and in order of listing, he gave the reasons for leaving England and for choosing Massachusetts Bay as: carrying the gospel to the new land; God had possibly chosen it as a refuge for those he would save from the “general destruction”; an indictment of treatment of the poor; the rising cost of living; the fountains of learning and religion had been corrupted; overcrowding; the establishment of “a company of faithful people”; a plea to the prosperous middle classes to go, setting an example to others.

6.1 Economic factors encouraging emigration

The main argument against economic problems being the cause of emigration to New England in the 1620s and 1630s is that the problems that existed had been there well before the 1620s. Inflation, particularly rising food prices, had been a problem since the previous century. A slump in the cloth trade, damaging an important industry in areas many New England emigrants came from, resulted from competition from the Dutch, including their prohibition on cloth imports, and loss of the Baltic trade, but the problems started after 1614, whilst the rush to New England did not really get going until 1634. Cloth trade problems could certainly have been a factor in earlier emigration to Virginia from 1603. Nevertheless, parts of East Anglia undoubtedly suffered severe slump in the early and mid-1630s, a possible incentive for a renewed move to emigrate; but in Sandwich, from where the Hercules sailed, and in Canterbury, the situation was less severe; the New Draperies of the immigrant Dutch and Walloons were thriving.

Table 2, earlier, showed that 28.6% of adult males on the Hercules, excluding servants, whose occupation is known, were involved in the textile trades: three tailors, a mercer and a hempdresser. Silk, at the top of the scale, and hemp at the bottom, were unlikely to have been much affected by the problems affecting woollen cloth and tailors worked more to the local market, so none of these should have been the worst victims of the slump in cloth exports. Many emigrant textile workers were in any case unable to have continued their trade in New England where no such trade existed. Virginia Anderson suggests one in four New England settlers had worked in the cloth trades, and the failure to establish a thriving textile industry was because the industry was too labour-intensive. The new colonies still had to concentrate on the most basic needs. Probate evidence shows that some took their looms with them, possibly assuming, on emigration, they would be continuing their trade. Tailors may not have been affected by these problems in the colony, however. Comfort Starr’s 1659 will left his house at Ashford, on condition that the beneficiary send to every one of the testator’s New England grandchildren “good Kersey and Peniston cotton, to the worth of 40s apiece”. The request for cloth rather than clothes suggests a role for tailors in the colony, but a definite shortage of cloth.

On the question of employment generally, decline in the cloth trade caused less hardship in Kent than some other counties. The same applied to the loss of Kent’s iron industry. As Zell and Chalklin point out, Kent had raw materials and waterpower, as well as proximity to the expanding London market. The county was able to diversify into new industries: paper, copperas, building materials and consumer goods. Maidstone, home of some Hercules migrants, was established as the major area for the production of thread in this period. Unemployment was thus probably not a factor driving people to emigrate from Kent in the 1630s to the same degree as from some other counties. Further, Flisher and Zell consider that the decline in the market for Kent cloths only began in the mid-17th-century, long after the Hercules sailed. Salerno’s research on the greater degree of hardship amongst Wiltshire weavers has already been discussed in chapter 4.

However, Richardson considers that wars with Spain 1625-30 and France 1627-9, combined with manipulation of the currency overpricing English cloth, and factors such as plague, all combined to devastate the cloth trade of the Weald and well as Sandwich, affecting shipping merchants and mariners too. He provides no details concerning the Weald, but in relation to Sandwich says that recession was under way in 1623 and absolute in 1627, and at times in 1622 three-quarters of Sandwich’s population were without bread corn. A downturn in trade and thus of shipping at Sandwich may have accounted for the problems of David Ketcherell, likely father of servants Joseph and Symon on the Hercules, which may even have been a factor in their decision to emigrate. In 1624/5, together with Isaak Cogger, he took a seven-year contract to operate the crane at the wharf at a rent of £20 p.a., but by the following year, now with Isaak’s son Joshua, had run into financial difficulties. They were indebted for money for the farm of cranage and because fees had not been paid for carriage of butter. Isaak Cogger covered the debts and continued to farm the crane alone.

The once prosperous port at Sandwich had been in decline since silting of the haven began in the mid-16th-century, but this, and the mid-1620s slump, seem too early to have prompted the emigration from there which began with the Hercules in March 1634/5. Indeed by the 1630s the town was recovering a little. Richardson notes some upward trends: from 1627/8, 224 bushels of apples were shipped from Sandwich to Newcastle; more affluent people in the town and region were importing luxury comestibles including sugar, currants, raisins, olive oil and tobacco. Figures by Ollerenshaw also suggest that in Sandwich in the 1630s the civic elite, amongst whom she names Hopestill Tilden, Nathaniel’s brother, were still financially strong. In inventories for the Sandwich civic elite 1630-39 she found 41.2% between £100 and £599.19s, another 11.75% over £600 and 11.75% over £1000; an overall total of 64.7% over £100. That compared with figures for the civic elite amongst English inventories 1570-1640 of 53.8% between £100 and £599.19s, and 12.6% over £600; totalling 66.4% over £100.

This suggests that while some emigrants were possibly driven from England by high prices and lack of opportunity, this was probably not the case for their richer companions who may instead have been drawn by the financial opportunities in New England both in terms of acquiring land an establishing new trade. Virginia Anderson stresses that the promotional literature for New England settlement was deliberately designed to winnow out people who placed economic welfare above all other concerns. However, as already seen, Nathaniel Tilden had close family connections to the negotiator of the Mayflower’s patent, to one of the earliest settlers of Plymouth and to one of the financiers of the Mayflower and Plymouth Colony up to 1626. Very soon after the purchase of the Adventurers’ debts and takeover of Plymouth Colony by the Undertakers, Nathaniel Tilden himself went there and bought land at Scituate. Deane says it is certain that Tilden and six others were in Scituate before 1628, basing his statement on Tilden on his 1628 purchase of land adjacent to that which he already held at Scituate. From the same time, Undertaker and former Adventurer Timothy Hatherley, possibly already Tilden’s friend, started making regular journeys to Scituate, where he owned land from 1627. Pope described Hatherley as “one of the leading partners in Plymouth Colony” . Hatherley was to marry Tilden’s widow in 1642. Widows at that time often married within their husband’s social or family circle. This raises the question whether Tilden, with all his interesting connections, was himself principally an investor in the colony rather than a religious exile, despite his many Puritan connections. When he first went out in 1627 he may just have gone to invest in land, but liked the life he saw developing there, and decided ultimately to take his family to settle. If the planters suddenly bought out the colony and the debts from the Adventurers in 1626, they must have had an injection of money from somewhere, so perhaps investors like Tilden filled the gap. Similarly did Hercules co-owner, merchant William Hatch, who also settled in Scituate, go there to invest in new trading operations? Another Hercules passenger potentially centrally involved was Samuel Hinckley whose son became Governor of Plymouth.

In relation to Winthrop’s reference to overcrowding in England and available land in Massachusetts, Powell plays down the importance of land hunger driving people to New England, producing figures showing that, between 1617 and 1637, in three parishes that sent emigrants to Sudbury, Massachusetts (Berkhampstead and Northchurch, Herts. and Fresden, Wilts) 313 men gained land whilst only 119 lost it. However, in New England the opportunities to acquire land were huge. Those who founded towns, or were amongst the earliest settlers, received favourable land grants, with options on more land as it was released when the town grew.

6.2 Religious associations and problems

Clearly many of the people on the Hercules did have radical religious sympathies of some kind. The Starrs had classic Puritan Christian names; the inventory of Tilden and the will of Thomas Hayward both listed works by John Preston, Master of Emmanuel College and leading preacher against Laud, as well as Thomas Shepherd, John Dodd and other leading Puritans. Tilden also had Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, as did Comfort Starr. As well as Tilden’s family link to Separatist Robert Cushman, both he and Hatch had a connection through a bequest in the will of their uncle to Separatist preacher John Lothrop, whose memorial in Lothrop Hill Cemetery, Barnstable, sums up his career (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Memorial to. John Lothrop

As Tilden had radical connections and was apparently leader of the largest interconnected group on the Hercules, almost certainly the majority of that grouping were either Separatists or had strong Puritan sympathies. It does not necessarily follow that all on the ship were Puritans, though it seems unlikely that people who did not have some sympathy with Puritans would undertake such a journey with them. It also does not follow that their religion was the main or the only reason for this group going. Virginia Anderson looked for evidence of their persecution but found little. A search for Hercules passengers in the indexes to many volumes of Canterbury Consistory Ecclesiastical Court records 1615-34 produced several references to the Tilden, Starr, Besbeech and Witherell families, but most were matters such as a long-running dispute over a will, and non-payment of tithes (an indicator of religious dissidence, but not persecution). However Comfort Starr appeared on a schedule of four people excommunicated on 2 December 1618. Virginia Anderson also says that William Witherell had been in trouble with the church authorities, but gives no details. As a clergyman, this would however explain why he was a master at Maidstone Grammar School, with its connection to his Cambridge College, Corpus Christi, rather than having care of a parish. Nathaniel Tilden had not been mayor of Tenterden since 1622, and by the time his brother-in-law held the post in 1641, the religious tide had turned again and Laud was out of office, so it is not entirely clear whether Tilden still held his earlier position of respect in Tenterden by 1634, though there is no evidence he did not. Cressy considers that “whilst many may have felt threatened by the religious policies of Charles I and the Laudian bishops….only a handful had actually experienced religious persecution”. It is difficult to judge exactly what life would have been like for religious radicals in the 1630s in the parishes the Hercules emigrants came from. Parish visitation records that might have helped with this are currently unavailable. Yates speaks of steps being taken in both Rochester and Canterbury Dioceses in the 1630s to enforce the Anglican canons and prevent the appointment of Puritans to benefices. However the Weald, Ashford and St Mary’s Sandwich all had established communities of religious radicals, and few from the Hercules would have had to travel far to find a Minister they approved of. However, even without persecution or loss of position, the religious climate in England would have produced a general dissatisfaction with life in England amongst many religious radicals, making them more open to opportunities to create a new life elsewhere.

The picture emerges of people of various religious beliefs emigrating, a good proportion of them having some sort of Puritan beliefs, but not necessarily emigrating solely for that reason. Cressy reports that “unsuitable and unregenerate settlers repeatedly violated the godly calm of New England”, but “New England developed as a Puritan society despite the flaws and exceptions in the ‘Puritan migration’”, and “the Puritan alliance between the Courthouse and pulpit created a religious culture unparalleled in the English-speaking world”. Cressy also says that much Puritanism developed post-emigration because “secular migrants who emigrated for social or economic reasons found themselves at a disadvantage if they did not join a church”. The religious radicals amongst the earliest settlers would soon have been able to take control fairly easily because of the high numbers of radical clergy amongst them, and because men amongst them like Tilden, Starr and Austen had money, position, good education and experience of office.

6.3 Other possible reasons for leaving England

New England was no doubt seen as a likely refuge from the constant epidemics of England. Sandwich itself had outbreaks of smallpox and purple ague in 1624 and plague in 1625. While not that recent in 1634, their recurrence must have been a continual worry, and in fact Sandwich was to suffer plague again in 1636. Shortly before he bought his land at Scituate, Tilden himself lost step-brother Robert Cushman, then on a return visit to England, to plague in 1625.

Further worries were the Spanish and French wars of the 1620s. In Sandwich the nightly watch was re-established in 1626; a levy on coal to pay for ships was imposed; 200 men were pressed for service from the Cinque Ports and Kent and Sussex coastal towns; soldiers were billeted in Sandwich in 1628; Sandwich was ordered to provision 1400 men in November 1628: and £260 Ship Money levied on the town in November 1634. Tyack relates strong popular feeling against shipping levies in East Anglia in 1627 and 1628.

Peer pressure was another compelling factor. Sections 4.6 and 4.7 above saw some of the connections the Hercules passengers had with people who went with them, ahead of them, and who followed. Fear of losing loved ones forever would have been a strong incentive to go with them, and may have been a partial reason behind the complicated web of connections found both between people on the Hercules and between them and other settlers. People were also influenced by the literature of the Massachusetts Bay Company, some of it very over-favourable propaganda, and by the sermons of some Ministers urging them to go.

A remote destination like New England would have been a very effective place to hide from the authorities, creditors, or from family problems, but it must surely be assumed that most would have chosen a more comfortable hideout, without all the hard work and deprivation that life in early New England would entail, and that the dissolute would not knowingly choose a lifetime in the company of the Godly and righteous.

Cressy considers that whilst much was made at the time about the role of the planters as missionaries of the gospel, “conversion of the Indians never claimed more than a fraction of the Puritans’ energies”. Tyack did however find an example: Rev. John Elliott, originally from Essex, who became known in New England as “the saintly Apostle to the Indians”. No doubt a few fugitives and missionaries did add to the mix in the new colony. Yet another factor, for a few at least, may therefore have been adventurism or pioneering spirit.

A factor rather understated by many secondary sources is the sheer size of the undertaking: the distance, the journey into the unknown, the uncertainty about safety and security both on the journey and on arrival, the unlikelihood of ever being able to return. Those most able to accept this challenge were likely to be free-thinkers and thus the better-educated, exactly the sort of people who were also more likely to be radicals, not only in religion. Many of the emigrants to New England came from Kent and East Anglia. Situated between Continental Europe and London, these were the places, after London, where new ideas first emerged. These were the counties most involved in Jack Cade’s Rebellion and the Peasants’ Revolt. Gavelkind had produced more people of the more independent middling sort in Kent, and in many parts of East Anglia similar partitive inheritance systems produced similar results in the structure of society.

6.4 The choice of New England over other destinations

All of these factors were possible motives for people to leave their local area, and even England, but do not fully explain their choice of New England, when they could have chosen Holland (as in fact 414 emigrants from Yarmouth alone did in 1637), or one of the more developed American colonies that would have entailed a lot less hardship.

For those motivated by religious difficulties, the nearer refuge of Leiden had already worn thin for many, largely due to restrictions on trade for strangers there. Though people were still going there from England in the 1630s, the Mayflower pilgrims left in 1620. Their decision to settle in Plymouth, whether the initial landing there was accidental or not, put them outside the jurisdiction of the Church of England which applied in more settled Virginia. It was Plymouth, and subsequently Massachusetts Bay, which offered comparative freedom of religious practice.

For the economic migrants, though the hardship was greater in New England, so were the potential economic rewards. In Virginia and other American colonies, the best land had already long been claimed and the best trade deals had probably been done.

7. Preparing for the Journey

In a new colony with very little industry or distribution network, settlers were advised to take enough food to feed themselves until their first New England crops were harvested and animals reared, as well as half a hogshead of salt to preserve fish, and all the tools, clothes, bedding and arms they would need in the first year. Several catalogues of the items required were produced. Cressy reproduces both advice from 1630 which is flexible according to the settler’s means, but shows items to the value £17 7s 9d as a minimum, and the slightly later list of John Josselyn suggesting items per man to the value of £30 3s 1d to last one year. With fares, the former list might be assumed to translate to an expense of around £70 for a family with four children, on top of the money they would need for things they could buy in New England: the wood to build a house, land to build it on and perhaps to farm. As well as arranging for their passage, they would have needed time to raise money to buy the essentials, and further time to buy and pack them. If they owned a house or land they would need to arrange to sell it or rent it out. Both Tilden and Starr kept and rented out their houses and land at Tenterden and Ashford respectively, but Tilden made no mention in his will of the land in Guldeford, Sussex he had inherited from his father.

The picture painted in many of the secondary sources is of emigrants to New England sailing entirely into the unknown. In fact, as Cressy demonstrates, many were very well-informed through letters from friends and family who had gone before them, though published accounts of the colony varied between the over-enthusiastic and the over-critical. Whilst a search of the 35 passenger lists of ships that sailed from England to New England between 1620 and 1635 on the incomplete Pilgrim Ships List found none of the Hercules passengers making earlier visits, it has already been seen that at least one, Nathaniel Tilden, had been before, suggesting the Hercules trip was very well planned. Tilden is not however named on Lothrop’s list of houses at Scituate dated October 1634 (Appendix 7), so it would appear that whilst he had been buying up land he had not properly lived there. Of course it is possible that he did not buy the land in person, but the acquisition of two parcels of land, one in 1628 and one earlier, suggests he did visit before finally settling in 1635. Savage suggested that Thomas Hayward had first been to New England with Winthrop in 1630 and, liking what he saw, returned to bring out his wife and family; but Robert Anderson considers it unproven that this was the same person. The Hercules passenger list shows that Margaret Johnes’ husband William had gone out ahead of her, presumably to make things ready.

Clearly emigration to New England was expensive, and took a lot of lengthy planning. The only way to avoid the cost and the time delay would have been to sign on at the last minute as somebody’s servant. Those who were fugitives of any type probably did just that, where possible.

8. Destinations and Outcomes

This section looks at what the settlers did when they arrived in New England. Did they form a community together? What offices did they hold? What were their other achievements? Were they likely to have particularly influenced later perception of early New England?

8.1 Establishing communities together

Appendix 8 shows where the Hercules passengers initially settled and the subsequent moves they made. It can be seen that of 85 people for whom first destination is known, 40, almost half, settled at Scituate; 17 at Cambridge; ten at Charlestown, one family of eight at New London, and other very small groups or individuals elsewhere. Comparing this to Appendix 4 showing connections between the passengers, and Appendix 6 showing 31 people (five families and seven individuals) with family, parish or possible connections to John Lothrop, who himself settled in Scituate with his followers, it can be seen that to a small extent, groupings from the Hercules split on arrival in New England. The main grouping, which settled at Scituate, centred on the Tildens and their Hercules co-owners the Hatch family, but did not include third co-owner Comfort Starr and his family, or the Tildens’ relatives and fellow Tenterden civic elite the Austens. The Starrs and Austens went to Cambridge, along with the Haywards from Aylesford who, from English records, had seemed unconnected to other passengers. The Scituate group did include Tilden’s possible relatives the Besbeech family from Biddenden/Sandwich, Tilden’s friends the Witherells and also the Hinckleys, who may have been part of the Tilden/Austen group at Tenterden.

The other main grouping of those associated, or possibly associated, with John Lothrop also split on arrival. This group consisted of Lidia Tilden and William Hatch, both of whose uncle John Hatch had left a small bequest in his will to Lothrop, though never associated with the parishes where Lothrop or his father-in-law preached; Parnell Harris, and her step-brother James Sayers, whose siblings were in prison with John Lothrop due to their religious practices; and several people who lived in or very near the parishes where John Lothrop and his father-in-law preached and may have been influenced by him. The Tildens and Hatches provided the crossover between the Lothrop group and the main group and, as seen, settled in Scituate. Of the rest of the potential Lothrop group, only servants Jenkins and Holmes, who both lived near Lothrop/Howse parishes and may have possibly been influenced by them, went to Scituate. Even Parnell Harris, and her siblings who had been imprisoned with Lothrop, settled in Providence. However, Lothrop and Howse may still have influenced some of those from surrounding parishes, as some were amongst the small groups who went to Charlestown and Salem, both of these Puritan settlements where many of the second phase coming out of Leiden had settled in 1629 and 1630.

John Lothrop himself was released from prison in June 1634 and went to Scituate with a group of his followers variously estimated as 30 or 40. They were certainly in Scituate by Spring 1635, so Lothrop’s plan of houses in the town (Appendix 7) beginning with the September 1634 layout may indicate that those were houses that were there just ahead of their arrival. With just nine houses and nine families in Scituate in September 1634, it seems that the arrival there of Lothrop and his followers followed by forty from the Hercules in early summer of 1635 really was the birth of a new community, and going there to form it was the purpose of almost half the Hercules passengers. Central figure Tilden had bought his land there over six years earlier, and probably knew at least one of the nine already there, his brother Joseph’s Adventurer colleague Timothy Hatherley. Clearly Scituate was not a chance destination. How many of the other Hercules passengers pre-planned their destination is less clear. Some may simply have looked for opportunities after they landed.

In contrast, whilst of 80 people on the Elizabeth from Ipswich to Massachusetts Bay in 1634 whose destination is known, 58 men women and children settled together in Watertown, they chose a town that had been established four years earlier. The first settlers had been a group of 86: 21 families and 13 single men, mostly from East Anglia but led by Sir Richard Salstonshall of London and Rev. George Philips of Boxted, Essex. Sir Richard had been elected an assistant of the Massachusetts Bay Co. in 1628/9 and had sent servants and cattle ahead in 1629. He returned permanently to England in 1631. It has not been discovered whether the group on the Elizabeth were generally known to each other in England. They had no obvious pre-existing links to Salstonshall or Rev. Phillips. The settlement of Watertown seems to have been largely engineered by the Massachusetts Bay Co., whilst the earliest settlement of Scituate seems to have been orchestrated by Nathaniel Tilden and others, perhaps including the Adventurers. Tilden may well have arranged things for the Lothrop group, as Lothrop himself seems unlikely to have had time between his release from prison and departure to New England.

8.2 Office-holding, achievements and influence

Appendix 3 shows information about offices held by the Hercules emigrants, and their families. This is very incomplete, the English information being restricted to town records of Tenterden, Maidstone and Sandwich, and the New England information coming only from secondary sources. Nevertheless, it shows the background of the Tildens and Austens within a civic elite in Kent. In New England it seems that a high proportion of the very early male settlers became freemen and took on posts of civic responsibility. A brief survey of the men from the Elizabeth which sailed from Ipswich to Massachusetts Bay in 1634 shows that their experience of freeman status and office was largely similar, though they boasted no future Governors amongst their sons.

As already seen, Comfort Starr was probably the son of a graduate of Emmanuel College Cambridge. He himself, as a surgeon, did not have an English university education. Doctors at that time were either apprenticed or studied at Leiden or Padua. It seems likely that Starr’s motive for emigration was to do with the founding of Harvard University. On arrival he apparently went direct to New Towne, which was renamed Cambridge in 1638 to reflect the number of Cambridge graduates who lived there. Starr may have been interested in Harvard’s early intention to include the teaching of medicine. That he was very keen on education was demonstrated by his will which left his grandson Simon Eire £6 p.a. provided he continue to pursue his studies in “tongues, artes and science”. Comfort is widely credited with having been one of the earliest benefactors of Harvard, though no contemporary authority for this has been found. However a current guide to Boston, in its section on the King’s Chapel Burial Ground, refers to the grave there of “Dr Comfort Starr, founder of Harvard University”. A plaque in Cranbrook church (Figure 4) further bears this out.

Figure 4: Plaque Commemorating Comfort Starr in Cranbrook Church

In Memory Of DR. COMFORT STARR Baptized in Cranbrook Church, 6th Jul 1589 A Warden of St. Mary's, Ashford, Kent, 1631 & 1632 Sailed from Sandwich for New England, 1635 One of the Earliest Benefactors of Harvard, the First College in America, 1638 Of which His Son Comfort was One of 7 Incorporators, 1650 Died at Boston, New England, 2d January 1659 A distinguished Surgeon Eminent for Christian Character Erected by His American Descendants 1909

However, Morison surprisingly makes no mention at all of Comfort Starr senior, except to question the claim that it was his house in Boston which was used to establish the College in 1636. Comfort Starr’s son, Comfort junior, graduated from Harvard College in 1647 and was one of the five founding fellows named in the University’s 1650 Charter, but again Morison makes no further mention of him except that he shared rooms as a student with the sons of Governor William Bradford and prominent Minister John Cotton, fellow of Emmanuel College.

A 1998 article in the Harvard University Gazette concerning endowments made to Harvard Medical School and Kennedy School of Government by Comfort Starr’s direct descendant, journalist, lawyer and adviser to the United Nations, William Starr, said that the house where Comfort Starr established his surgery practice in 1635 was, “according to family history” where Nathaniel Eaton, in 1639, began Harvard College instruction. Whatever the exact truth about the involvement of Comfort Starr in the founding of Harvard, this prominent family still had the ability to perpetuate the story to an audience 350 years later, and over the generations would similarly have had the ability to have their view of the ‘Great Migration’ accepted by many. From the Hercules, the Tildens and the Hinckleys were at least two more families who certainly did have continuing capability to influence people and thus perceptions of the nature of the early settlers. Nathaniel’s direct descendant Samuel Jones Tilden was Governor of New York and Democratic presidential candidate in 1876. Several volumes of letters and papers of Thomas Hinckley, son of Hercules passenger Samuel, were published as late as the 1860s, though now seem now to be unobtainable. The influence of his descendants continues however. Although no definite documentation has been found, prominent people who have claimed, or have been claimed, to be descendants of Thomas Hinckley or of his sister, so descendants of Samuel on the Hercules, include both the Presidents Bush, Sarah Palin and Barack Obama.

9. Conclusion

The in-depth research into the Hercules emigrants shows that in many respects they were fairly typical of emigrants to New England from 1628-1640. The unusual or unexpected characteristics of the Hercules group to emerge were their high representation of the civic elite of the towns they came from, their high number of connections to university-educated people, their complicated interconnections, and the strong connections of central figure Nathaniel Tilden to key figures in Plymouth Colony’s earliest history.

Considered in the light of secondary source material, the research suggests that although the majority of the emigrants were either religious radicals of some sort or had some sympathy with them, their radical beliefs sometimes developing or strengthening after arrival, even amongst this group, religion was not always their principal or only reason for going. Radical religion was perhaps co-incidentally strong both in many areas the emigrants came from, such as Kent and East Anglia, and amongst the textile workers who were both strongly-represented amongst the emigrants and suffered financial hardship in some areas. Economic motives were of two types: economic problems (less marked in Kent than some other areas) driving people to emigrate; and economic opportunities and particularly the availability of land, drawing people to the new colonies.

Whilst a strong argument supporting religious problems as a key reason behind the ‘Great Migration’ is that it exactly coincided with the period of William Laud’s dominance, this cannot be seen as a religious flight for the majority. Not only is there little evidence of many of them actually being persecuted, but arrangements in terms of financing the trip and getting together the enormous quantities of necessary supplies took too long. Some, such as Lothrop after release from prison, may have been helped by others to leave quickly; but for most emigration was a lengthy business more in keeping with a considered purpose than flight.